- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Behind the Scenes of the Theo Series - Production

The Pre-production phase (see last blog) is now complete and Production is ready to begin. This phase––consisting mainly of layouts, animation, cleanup, background painting (BG) and color modeling––is the busiest, most time-consuming phase of making an animated film. It’s where the rubber meets the road or, more accurately, where the pencil meets the paper. Lots and lots of paper and pencils and erasures.

It’s a very involved process, and I can only give the broad strokes in one blog. So let’s begin with layouts.

Just as a live-action production needs locations and sets in which actors will play their scenes, so also an animation production must have locations and sets in which the animated “actors” must act. However, instead of scouting locations and building sets, in animation a layout artist must draw them.

A layout artist is simply one who lays out––or plans––a scene. What does that mean? First of all, layouts include both background (BG) layouts and character layouts. Let’s talk about BG layouts first.

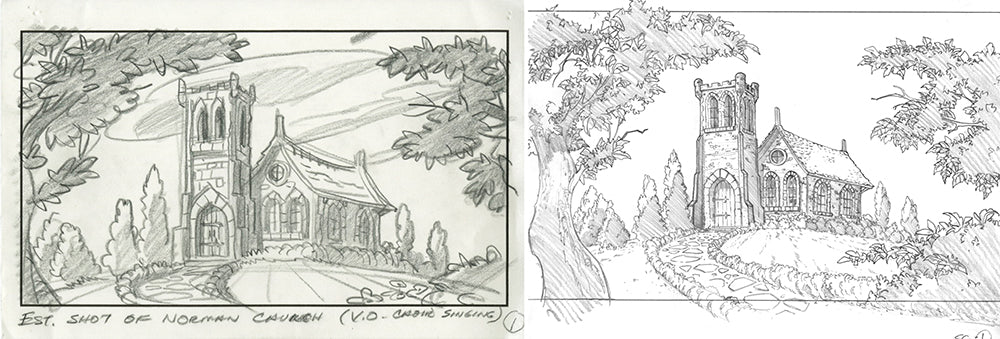

If the script calls for a BG––say Theo’s cottage, mouse hole, Theo’s library or whatever––then it’s the job of the layout artist to design what that environment looks like. Exactly what it looks like. If it is Theo’s cottage, for example, the layout will show windows, and thatched roofing, and bushes and trees––everything the scene should look like before it is actually painted.

The layout artist usually begins with a storyboard scene, for, as I stated in my last blog, the storyboard is the blueprint for the film. It sets the stage (pun intended) for everything that follows. Because storyboard panels are typically smaller than full size animation paper, the layout artist will draw the scene to scale; that is, to the actual size the animator will animate to.

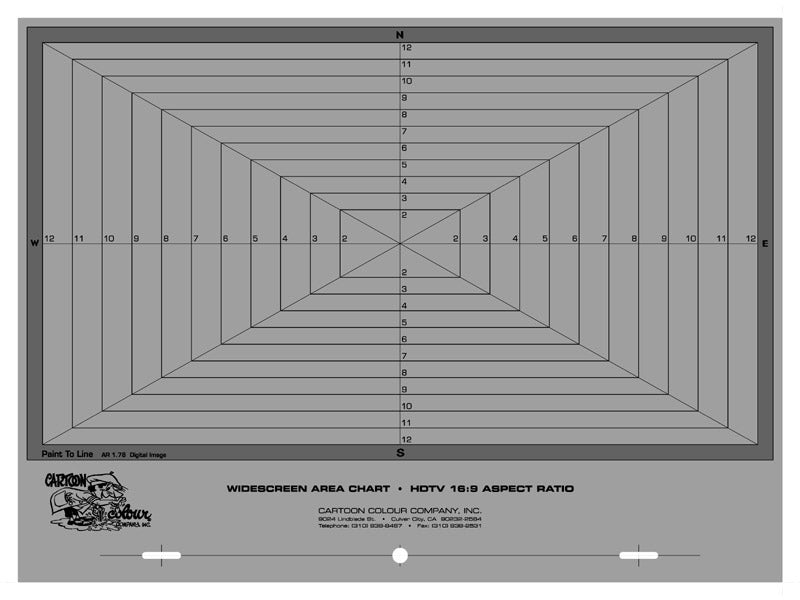

At this point I could write scads on the technical use of field guides and aspect ratios, field cuts, truck-ins and truck-outs, vertical and diagonal pans, which might cause the reader’s eyes to glaze over (I’m getting sleepy just writing this). So, for the sake of humanity, suffice it to say that most animation is drawn within a 12 field setup, with a 16:9 aspect ratio (widescreen), which fits most modern television and computer screens. (see photo of a typical 12 field field guide).

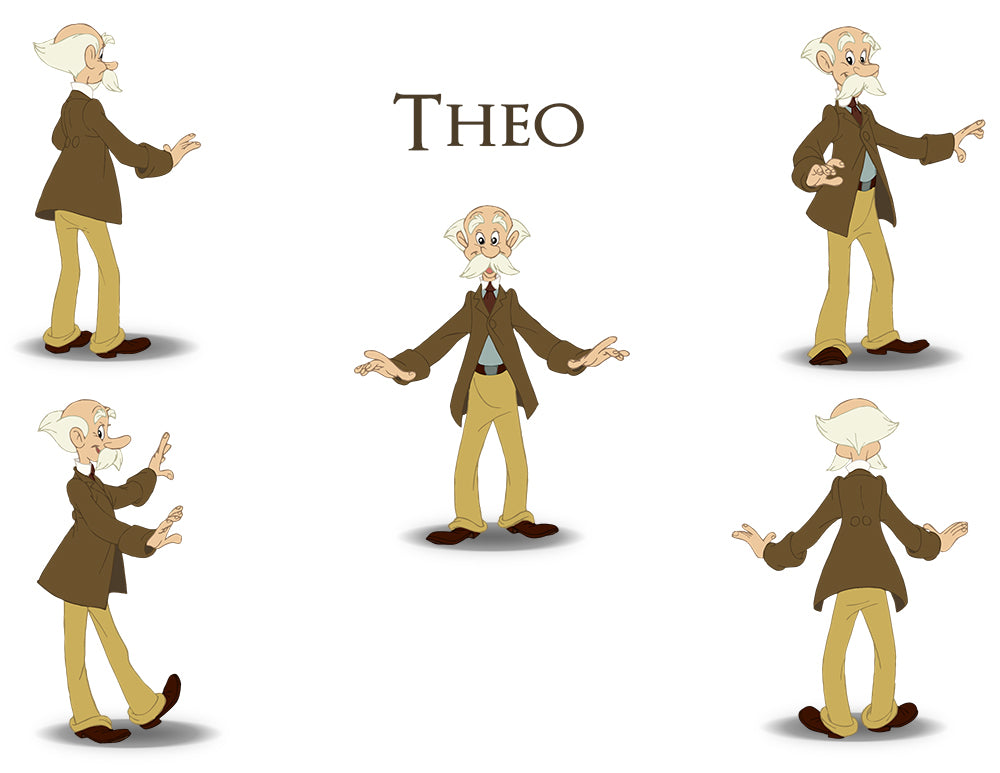

As I said earlier, layouts contain two components. Apart from the BG layout, a layout artist must also include rough drawings of the characters that will animate in that particular scene. Say for example that the scene requires Theo talking with the mice. If so, then the character layout will show “pose drawings” of what Theo will do in the beginning, middle, and end of the scene. He will be drawn “on model”; that is, according to the model sheet described in the last blog. This way we get a consistent look for Theo and the mice, as well as their relative sizes; and, more importantly, the animator will know his start and stop marks. Indispensable in producing quality 2D animation.

Finally, a layout artist will indicate various movements of the camera to the animator. For example, we might start the scene at the little Norman church overlooking the river, then PAN over to Theo’s cottage where we see Theo talking with the mice. A PAN is when the camera appears to move from one part of a background to another, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Somebody’s got to indicate this stuff. It probably was written in the script, indicated in the storyboard, but now visualized in the layout.

At this point production approaches a fork in the road with three tines (technical jargon for heading this-away and that-away at the same time). In reality they are three separate roads that diverge after the layouts. One road leads to background (BG) production, the other to traditional 2D animation. A third road leads to our Shoebox Bible Theatre production (the part of the show where Theo tells a Bible story through stylized computer-generated animation), which I will discuss in a future blog.

Let’s talk about BGs.

Since that opening scene every Theo BG has been painted digitally in the computer by very talented digital painters. Being a Neanderthal when it comes to embracing New School technologies, I was resistant to this at first. And then I saw what the new stuff looked like, how BGs could be modified, and given multi-plane effects (next blog). It’s truly amazing!

In the old days BGs used to be painted by artists using paintbrush and actual paint (gouache, watercolor, cel vinyl, etc.), depending on the production design of the picture. As a point of interest, the opening pastoral scene in Theo’s The Good News was painted this way, by Annie Guenther. This dear lady started at Disney studios as an inker (more on this next blog) on Sleeping Beauty (1953), and was a BG painter on Robin Hood (1970). I have left that opening BG intact in her honor, and as an homage to the Old School BG painters.

Colors for the characters are usually chosen at this point, so that they will work well with the BGs. Theo’s fishing togs must show well against the BG. Likewise, the mice or Scratch or Bumper or Bailey must appear natural against their BGs. If not, they won’t read or feel right. They’ll seem unnatural. Further, there are daytime colors and nighttime colors. In our episode on “What is the Church” (God’s Heart) the opening sequence is outdoors and at night and needed a spooky look. So the colors needed to be chosen to work with the BGs. If we don’t choose colors with the BGs the illusion of simulated life will not work.

Now for the second tine in the fork.

We now take the road that leads to traditional (2D) or traditional animation. I love classical animation, the kind Walt Disney was famous for. I also love the 1950s graphic cartoony look that dominated the late-1940s and 50s television and print ad work. So I have included both of these approaches in our Theo episodes to provide variety, visual interest, and hopefully humor.

The stage is now set (drawn), the characters are in costume and at their marks, the director calls, “Action!” to the animator, and off we go.

An animator is an actor with a pencil.

The primary job of an animator is, like a live-action actor, to make a character believable. His challenge is to make a character so appealing or menacing or funny––whatever––that viewers will actually believe that the character is real. That the character actually thinks, that he feels. Remember, an animator must do this with a pencil. If the animator has caused me to suspend belief––that is, to not think that I’m really watching a series of drawings flying by a 24 frames per second; if he causes me to laugh or cry or bite my nails, then he has done his job.

Two of my favorite A-list animators of the modern era are John Pomeroy and Len Simon. Both of these versatile animators are seasoned pros who have worked in top studios like Disney, DreamWorks and Sullivan Bluth Productions, but now work on Theo. I am both blessed and honored to have men of such talent on the production team. I love getting scenes from these guys, because I know that the vision I have for a character or scene will always be surpassed by these super talents.

John started animating at Disney, and along with Gary Goldman and Don Bluth, founded Don Bluth Productions (An American Tail, Land Before Time, The Secret of NIMH). John was thrilled to be a part of an animated series that glorified the Lord. Len Simon cut his teeth at Sullivan Bluth Studios (Thumbelina, Anastasia, Titan AE) and soon became their youngest animation director. Truly a wizard with a pencil.

Neither of these guys live in Southern California where Whitestone Media is located, so how do I see their work?

Pause for a Time Capsule moment.

Back in the Stone Age animators used to work in a brick-and-mortar studio alongside other animators and artists. This promoted studio camaraderie. It also promoted a healthy competition between artists. Animators could see what the animator in the next room or animation desk was doing and be inspired by his work. You could also go to some veteran animator who had been with Walt Disney or Friz Freleng or Chuck Jones in the early days and ask for advice on a scene. When I first got into the animation business in the 1970s this is how it was. I miss those days, and I miss the studio system (I sound like an old geezer, don’t I), but time marches on.

Nowadays, the animator can live just about anywhere in the world he or she wants to live, as long as they have Internet access. Here’s how we do it now. After the animator has finished the first draft (or rough) of his scene, he scans it onto his computer and sends it to me via email or through some other Internet program. I can look at his scene on my laptop immediately, call him up and discuss it with him. There may be a change or two, but mostly, working with pros like John and Len, there are few. These guys have made my job as the director a joy.

Cleanup is the next step in the production process. Like the title implies, a cleanup artist is one who takes the relatively rough animation drawings of the animator and cleans them up; that is, he or she draws a clean line, making sure that every part of the character is drawn on model. The cleanup artist is a bit of an unsung hero. Most likely, unless the animator draws very very clean––or “tight”––the actual line drawing that you will see on the screen is the work of the cleanup artist. These are men and women with very steady hands, and with keen eyes for detail.

In a production with a limited budget the cleanup artist will usually draw all of the inbetweens (inbees) that the animator has left for him or her. In large productions with big budgets there is usually a separate department where Inbees are handled by inbetweeners. Clever name, huh?

People often ask me how many drawings go into a minute of film. My answer always produces an open-mouth, eye-popping response. To give you an idea of the enormity of the animation task, there are 24 frames of film (35mm) for every second. Everyone of those frames must have a drawing in it. Sometimes, two. Sometimes more, depending on the complexity of the scene. Let’s do a little math. Twenty-four frames times sixty seconds is 1,440. 1,440 drawings of ONE character for every minute of film! Two characters, double it. Three characters, triple it, and so on, times the number of minutes in an episode.

Holy carpal tunnel syndrome, Batman!

Thankfully, the human eye is very forgiving. Animators, in order to save their wrists and fingers, discovered that if they film a drawing two camera clicks, rather than every one click, we will still see a fluid movement in the drawings. This not only cuts down the number of drawings per second, it helps with cost as well.

Finally, once an animated scene is completed and has been signed off, it is scanned into the computer and then dropped into the animatic––the “timeline,” as we call it at Whitestone Media (see last blog). In this way we build the episode one scene at a time, until all of the animation for the episode is completed.

Once the last scene has been animated, cleaned up and put onto the timeline, the production phase for that particular episode is officially over and Post-production begins. Technically, in order to maintain a good flow of production, post-production will overlap the animation process, as we shall see in the next blog.

And there you have it.

Next blog: Post-production

Michael Joens

Author