- Continue Shopping

- Your Cart is Empty

Behind the Scenes of the Theo Series - Post Production

POST-PRODUCTION

The term post-production refers to the final leg of production, where everything comes together in a kind of grand finale. Although post-production implies something that happens after production, “Post,” as it is simply called, is very much a part of the actual production process. Many elements that contribute to the finished picture occur in Post: ink and paint, compositing, music score, sound effects, and final mix.

As I mentioned in my last blog on Production, elements of Post will overlap the production phase. For example, once an animated scene has been cleaned up and scanned into the computer it moves, technically, into post-production. To wait until all scenes in an episode were finalized before beginning Post would cripple a production flow and extend the schedule needlessly.

The Post phase is the most technical production-wise. As I mentioned in my first blog Whitestone Media is a “tradigital” studio; both traditional and digital. Post is where we mostly handle the digital in tradigital.

Let’s begin our discussion with Ink and Paint. Inking, first.

INKING

Back in the Old School days (1920s - 60s), once a scene was completed by the animator and cleanup artist it was hand-inked onto clear celluloid sheets (cels) with brush and pen, usually by someone with a keen eye and very steady hands. What I mean by this is that a blank cel was placed over an animation drawing and traced by the inker, using a black ink line for the entire character. This inking might also been done in what was called a “self-color” line. The self-color lines were chosen to match, accent or compliment, the various colors of a character––skin and hair tones, clothing, etc. Very time consuming, very expensive.

Very beautiful!

All of Disney’s early feature films (until 1961) were done this way, as were many of the Warner Brothers, MGM and Walter Lantz shorts (Bugs Bunny, Yosemite Sam, Road Runner, Tom & Jerry, Woody Woodpecker, etc.); however, the less expensive shorts were mostly hand-inked with a black line.

Still very expensive, still a classy look.

When Xerox arrived on the scene in 1960 with the Disney theatrical short Goliath II, and then in 1961 with the theatrical film 101 Dalmatians, most hand inking went out the door. Using Xerox, the drawings were copied onto a cel with a fraction of the time and cost. The animators liked this approach, because their actual pencil line work––the life of the line––was preserved on the cel; whereas the hand-inked line approach was, of course, second generation and very clean.

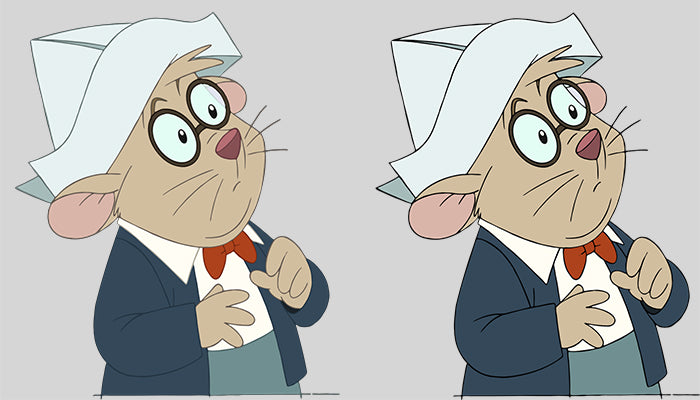

Today, for our Theo production, we actually have the best of both worlds available to us. Not only can we maintain the life of the animator’s actual pencil line, but we can do so using the self-color approach, without losing a generation. I love the look and feel––the richness––of the old self-line approach and insisted that Theo be treated this way. Next time you watch a Theo episode study the lines of the different characters, and you will see what I mean. You will get a glimpse of this in the Theo character shown here.

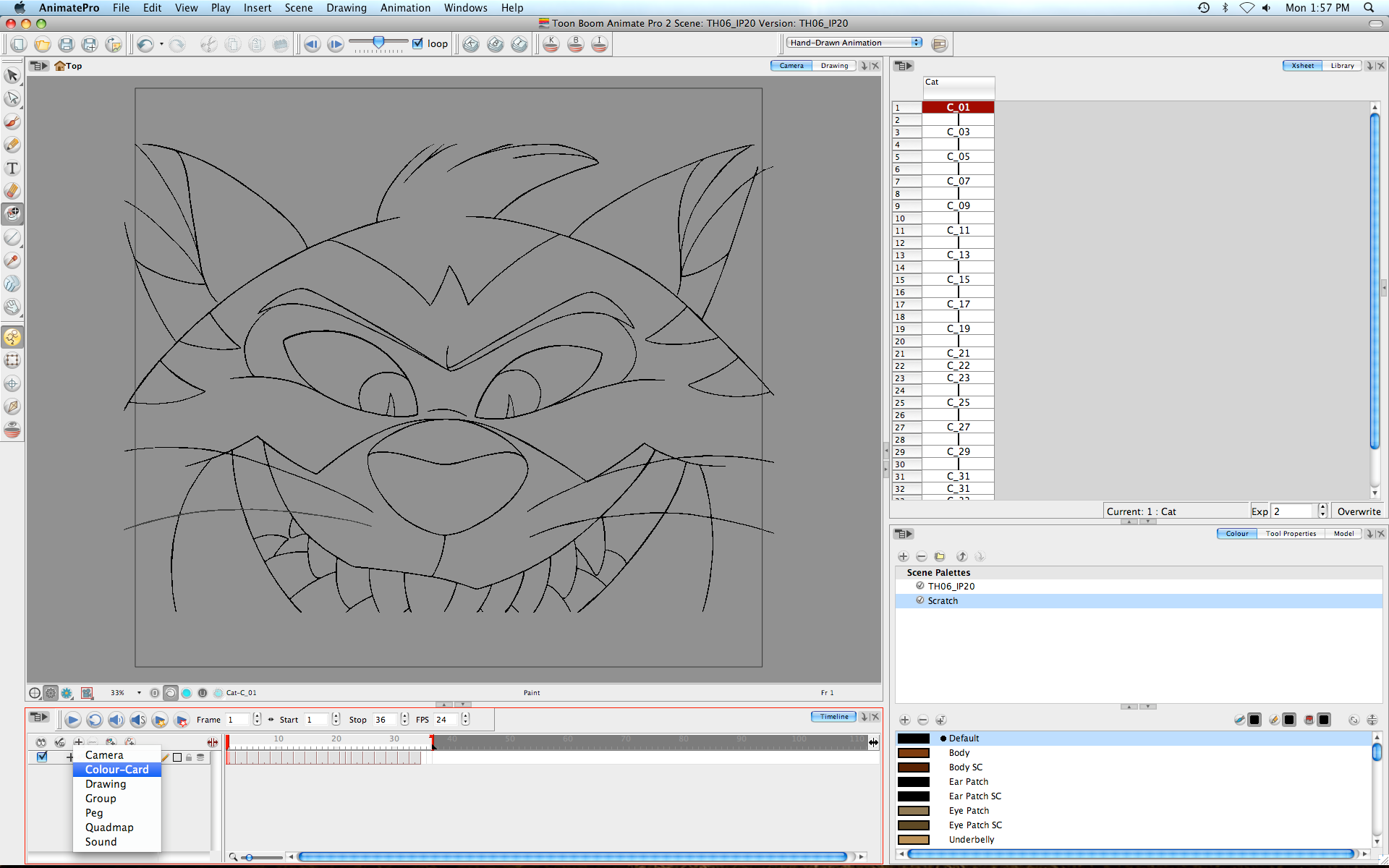

We can achieve this self-line look because of available computer programs like Toon Boom, and the computer wizardry of my Technical Director (Brandon Joens) and his crew. It still costs more than if we went with a solid black computer-generated line, but the more natural self-line look was worth it. Don’t ask me how these guys do what they do––probably because whenever Brandon wants to give me a tutorial I’m usually hiding under my desk.

So much for line work, now onto cel painting.

CEL PAINTING

Again, back in the Old Days, once a drawing was inked or Xeroxed onto a cel, it went to a cel painter. As a point of interest (to me anyway), my very first job in the industry, while taking an animation night class, was that of a cel painter at the Hanna Barbera studio. The job is usually handled by women (I hope this doesn’t sound sexist). They’re just better at it than men! When I worked as a cel painter there were 3 of us guys and 150 women. It’s a tedious job. Women have the patience and dexterity to do it well, and my hat’s off to them.

Once a cel painter received a scene full of celluloid drawings, she (or he) turned each one over and, using a cel-vinyl paint, painted (or floated) the colors into place––kind of upside down painting-by-the-numbers––then placed them on a shelf to dry. This process is now completely handled in the computer.

Nowadays a pencil-on-paper drawing is scanned into the computer. It is then cleaned up in Photoshop; that is, any lead smudges, or imperfections on the paper itself are digitally washed away. Once a scene is cleaned up it is dropped into the Toon Boom program and “vectorized” (don’t ask me what this means). Once all of the drawings in a scene are vectorized, the scene is ready for the digital painter. Zip, bam, boom. Done! Techie talk for it takes about 1/10th the amount of time as it did in the Fred and Barney era.

Very sad for the loss of jobs, but in this case the computer does it faster, less expensively, and without loss to quality. Hard to compete with that.

The next phase in Post is Compositing.

COMPOSITING

I never cease to be amazed at what the compositor can do today. Once a scene has been digitally “inked and painted” it is composited (or married) to the appropriate BG, which has been digitally “painted” in After Effects. At this point the compositor adds shadows and highlights onto the animated character, as well as what are called “drop shadows” beneath the character’s feet, planting it to the BG. This gives the character a real 3D look and feel, adding verisimilitude (techno term for “Man, that looks cool!) to the scene.

The compositor can also give a scene a real depth of field. If a character is walking in the scene with the BG panning (moving) behind him, the compositor can create a simulated parallax effect. What do I mean by this?

Imagine you are looking out the window of a car as you are zipping along the highway. Objects in the foreground––telephone poles, cows, trees, hitchhikers, appear to be moving faster than objects in the distance, don’t they? In reality they are moving past your eyes at the same speed. This is called the parallax effect. Today we can create this in After Effects. In 1937 Walt Disney’s William Garity and Ub Iwerks developed what was called a multi-plane camera, with several levels on which drawings, overlay paintings were placed, to help create a sense of depth and parallax. It took several technicians to operate it, but it created a cool verisimilitude. Check out the opening scene in Pinocchio to see what I mean.

For Theo we have used this parallax effect in several scenes throughout the series. The one shown here (photo A) shows the scene from the viewer’s point of view. This is a still photo, of course, so you don’t actually see the parallax effect in motion. However, we have provided a behind-the-scene look (or “behind the curtain,” as Brandon likes to say) at the many levels that are composited together, each moving at a different speed, to make this effect happen (photo B).

Finally, the compositor will color balance the scene/scenes, so that the picture, color-wise, all works together smoothly. Also, he can make scenes darker, lighter, moodier––whatever––and really “plus” the episode.

Now for the icing on the cake––Music and Effects

MUSIC COMPOSING

At the point when every scene in the episode has been composited and given a final edit by the director, the film is “locked down;” that is, it is finished/completed to the frame and won’t be added to or subtracted from. At this point the picture will be uploaded to our music composer.

In the case of a television series, a music composer will write several music cues––dramatic music, spooky music, happy music, traveling music, etc––and build a music library. A music editor will then select a particular cue to fit a scene or sequence, drawing from the library. This helps control cost, and is time efficient. But it is not action or scene specific. Next time you watch a modern cartoon (or live-action TV sitcom or dramatic series for that matter), you will hear music cues being used and reused. The process works, of course, much as a mass-produced piece of furniture works, but there is nothing like the quality of a handmade piece of furniture.

A musical score is the handmade approach. More expensive, but what a difference! Feature films are usually scored; that is, a composer will write music specific to the picture. No libraries.

The old Disney and Warner Brothers cartoons were scored back in the golden age of cartoons. One of the great composers was a man by the name of Carl Stalling, who worked for several of the big studios. Carl would score to picture, sometimes using musical instruments to accent a comedic moment, or to give a particular character a “signature” music theme. If you ever watch Disney’s Peter and the Wolf, you will see––rather hear––what I mean. This is the kind of approach I wanted with Theo. Each episode of Theo is individually scored to picture. There are no Theo music libraries.

We are blessed to have John Sponsler work with us.

John is a brilliant film composer who has worked with Hans Zimmer on the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise, and many other television series and films. He is also very Kingdom-minded, and has made himself available to write the score for every Theo episode. Next time you watch an episode turn up the volume and look away from the picture. There are several episodes, particularly in the Shoebox Bible Theatre sections, that are so moving that they bring tears to my eyes.

SOUND EFFECTS

Once the score is completed we send the episode to our sound man who adds sound effects (SFX) to the picture. We wait until our music is completed, because John Sponsler might have treated a moment on the screen with a musical effect, made by an instrument––woodwind, percussion, horn, etc––as Carl Stalling often did.

SFX come in two categories––effects and foley.

FOLEY

Foley (named after Jack Foley, who worked back in the silent film era) covers sounds like footfalls or doors opening, usually taped in a foley studio by a guy actually opening doors or making footfalls. Foley effects give necessary weight and sound to a scene. The old piano falling ten stories ending with a horrendous crash? You guessed it, foley! The helmet scooting over the floor in Theo’s “Armor of God” episode (God’s Grace)? Foley! The effect was created by our sound man, Brad Brock, in his foley studio, by sliding a pale over the floor. Not funny, per se, but without it the scene would be dead, sound wise.

EFFECTS

The other category of SFX is simply called effects. Effects accent the cartoon scene with sounds that are funny to listen to. They give a cartoon comedic punch. It’s the effects that make us laugh.

For example, an animated scene––say, the bulldog biting the bad guy on the fanny in our episode on “Salvation” (God’s Heart)––is funny to watch by itself. But when a wacky effects editor like Brad enters the scene, and adds the old “Bone-bite” effect to the precise moment, I guarantee it will evoke a belly laugh.

There are other scenes, like the swarm of bees attacking Luther at the end of the episode in “What is the Church” (God’s Truth), that utilize several layers of effects piled (layered) onto each other to create a specific sound. The sound I wanted was something like that of a WW2 fighter plane strafing a target (I know, I’m weird). Rising to the occasion, Brad combined the effects of various machine guns, jack hammers, buzz saws and who-knows-what-else, to create a very funny sound. Throughout the sequence the bees, shaped like an huge arrow, give Luther his just dues on his fanny as he runs away from the camera. (see photo) I can’t watch that sequence without laughing out loud (LOL to you social media users).

THE MIX

Finally, the last element of Post takes place in the Mix. Brad also does our mixing for us. He has worked as a professional mixer and sound guy in the cartoon industry for years (go to the IMDB site and check out his nearly interminable list of credits).

The job of the mixer is to “mix” or balance the various sound track levels––dialogue, music and SFX––so that everything sounds good and proper. For example, if the music is played too loud over a dialogue scene, then we won’t hear what the character is saying. Not good. Similarly, if a dramatic music score is played too low, we could lose the emotional underpinnings of the scene. Bummer. If a sound effect is played too high or low, then we may lose the scene’s comedic intent.

This brings me to tears.

And there you have it––the broad strokes, at least, of what goes into the making of a Theo episode. As I mentioned in an earlier blog, I will address the making of our Shoebox Bible Theatre (the Bible story sequence) in a future blog. For now, this should suffice to either whet your appetite for a more detailed look into animation production, or cause you to run out of the room with your hair on fire!

God’s best,

Mike

Michael Joens

Author